Following the publication of the 2020 edition of the market report “Mini-grids for village electrification Industry and African & Asian markets”, Baptiste Possémé, off-grid consultant at Infinergia, a consulting firm specialized on clean energy markets, analyses the African case.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), 320 million people have gained access to electricity between 2010 and 2018. However, the global population’s growth implies that more and more people have no access to electricity in Africa. They were 590 million at the end of 2018.

Three main solutions exist to power sustainably those populations: grid extension, individual systems, and mini-grids. The economical choice between those solutions is mainly linked to the distance to the grid, to the density of the population and to the level of service.

Grid extension is the most classical answer but has several issues. It can be extremely expensive for remote communities and does not necessarily offer a good quality of service (case of “bad-grid”). In its latest “Africa Energy Outlook“, the IEA considers grid extension as the least-cost option only for 45% of the population.

Individual electricity generation systems like solar lamps or Solar Home Systems (SHS) can provide at a low cost a basic quality of service to regions with low population density. SHS manufacturers or distributors (e.g. BBOXX, Mobisol, Fenix International, Total, Schneider Electric…) have experienced significant growth in this market over the last years. However, those solutions usually power low-power appliances and are usually used as transition solutions.

Mini-grids, local and isolated networks, have started to gain momentum in the last 5 to 10 years. In cases where the population is dense enough, they can offer a similar quality of service than grid extension as well as a lower cost than Solar Home Systems. It could represent the least-cost option for 30% of the non-connected African population.

At Infinergia, we analyzed the industrial context globally but also the projects and regulatory framework focusing on 21 African countries (and 11 Asian ones) where mini-grids are already a thing or could be one soon.

What is a mini-grid exactly?

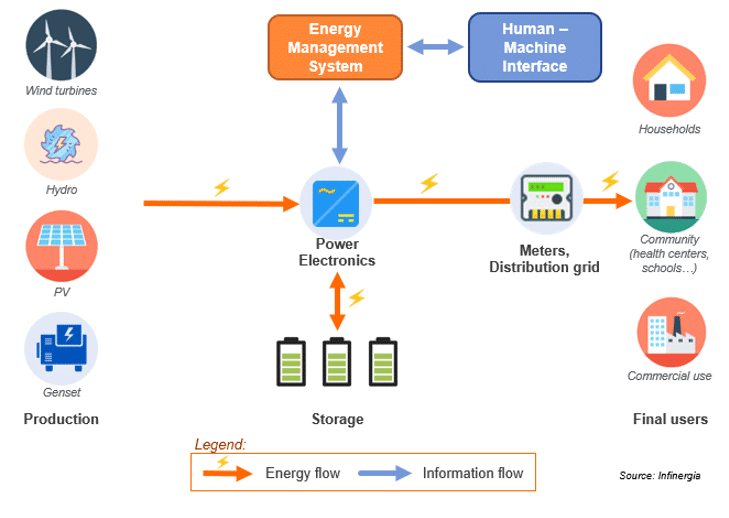

Mini-grids can be defined as one or several decentralized energy generation sources with a combined peak power between 10kW and 10MW connected to multiple customers through a local network. Those systems are completely isolated from the national grid. If they are not, we rather call such a system a micro-grid (more common in North America for instance). If the peak power is smaller (<10kW), we call it a nano-grid.

Most of those installations produce and distribute electricity at a community level (usually a village) but can also be used for commercial, industrial, military or agricultural applications.

They are not necessarily a clean source of energy. The first African mini-grids were often solely based on diesel. The drop in solar panel prices in the last ten years favored the development of solar-based mini-grids. Now, most recent installations are hybrid ones, using photovoltaic panels and batteries to have electricity at night but also are often connected to a back-up diesel generator to ensure a good quality of supply.

Main components of a mini-grid

Potential for 5,500 to 17,000 new solar mini-grids by 2026

In Africa, over 1,000 installed solar mini-grids have been identified. Most of them are in Senegal, Cameroon, and Nigeria. Among those, around 190 (around 20%) have been commissioned in 2019.

Regarding future projects, we estimate that between 5,500 and 17,000 new solar mini-grids could be built by 2026. To estimate this number, we have gathered, over the last 5 years, various announcements, tenders, and other national or private targets that we have double-checked with field interviews. In this context, it would be very optimistic to consider that all those announcements will lead in the short term to commissioned projects. In order to characterize their level of certainty, we decided to distinguish three main categories:

- Installed projects have been identified as such and should remain so in the next years. It should be noted that an unquantified part of those projects might encounter technical failures.

- Currently planned or in construction projects have been financed, tenderized and most of the time awarded to a company. They have a very high probability of ending up installed (even though delays may occur compared to the announced commissioning date).

- National or companies’ targets are engagements (usually not completely financed) that have been made by companies or countries to develop a certain number of mini-grids, usually with no precise location identified. They show ambition, but should be considered cautiously.

A Regulatory Framework Strengthening in Most African Countries but Still Uneven

At Infinergia, we have also developed an indicator to compare the development stage of the mini-grid market over 30 countries globally. By analyzing the regulatory framework, the announced and existing projects, the countries’ economic status and the local presence of mini-grid actors, we can compare, year after year, those countries’ evolution.

Compared to two or three years ago, most mini-grid national frameworks evolved positively in African countries. Eight countries (Ethiopia, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Rwanda, Zambia, Ghana, Mozambique, and Nigeria) reached a higher maturity stage. Over 75 public tenders for mini-grid projects have been published in the last two years, new regulations framing the development of mini-grids were released (e.g. tariffs, subsidies, private operators’ licenses, possibility to connect the mini-grid to the main grid…). Newly defined national targets for rural electrification include the development of mini-grids (e.g. Ethiopia, Kenya, Senegal). International funding to promote the development of off-grid solutions has increased (e.g. FEI OGEF, International Solar Alliance, World Bank…).

However, historical mini-grid markets like Senegal or Madagascar are still active in terms of projects but face uncertainties in the governments’ willingness to develop them. Some key answers and associated funding are still necessary to reach the various officially announced objectives.

Technological innovation is an answer to mini-grid difficulties but not the only one

Technical failures are common in African harsh environments. For instance, only 25% to 35% of the mini-grids installed in Senegal between 1996 and 2011 still work today. Batteries, for instance, are a key component of solar-based mini-grids. They are both the most expensive component and the most vulnerable to external conditions. A hot environment can thus have a decisive impact on the battery’s life expectancy. This is especially true for Lead-acid batteries that represent to date the largest share of installations. Furthermore, using various power sources adds a complexity that must be managed by an Energy Management System or EMS that needs to be both efficient and resilient in order for the smart grid to be sustainable.

At the system’s level, there is today a lack of standardization is the building process of mini-grids. Most mini-grids today are custom-made. Once the project is financed and the community needs have been established, an Engineering Procurement, and Construction firm (EPC) is chosen to design the most relevant system. A specific room is then built to host the different components (inverter, batteries…). The local workforce assembles every component on-site. Those systems are difficult to duplicate and to capitalize on.

To tackle those issues, more and more project developers use containerized standardized solutions. Such products can all be assembled inside the same factory and just then need to be distributed and unfolded (for the panels) on site.

Those systems have various advantages:

- They secure most of the hidden costs that often appear in custom-made projects (e.g. pieces missing, theft, the supply of various components, low quality of installation…).

- When produced at a relevant scale, they learn from each project and can have a continuous improvement

- Using such systems is also a path to more innovative components (e.g. new battery chemistries, more advanced EMS) on which the system integrator can have better control.

- In case of political or climatic instability or any threat to the equipment, the system can be relocated. This reassures investors and facilitates the development of the service.

By analyzing the main containerized solutions integrators’ projects (e.g. Redavia, Schneider Electric, Winch Energy, Africa Greentec…), we have identified 30 of such projects installed (not only rural electrification) representing 119 installed containers globally, by end-2019.

However, it should be noted that technical failures can also be caused by long regulatory delays (e.g. decision for subsidies selling tariffs, customs…) and better systems will not answer all issues.

These technical solutions are an important step towards the development of mini-grids. Nevertheless, long installation delays and some mini-grid’s failures can be caused by regulatory delays or political choices (e.g. choice of the cheapest system at the expense of its longevity, customs’ delays during which batteries wear out…). Technological innovation must not hide the fact that the main brake on the development of this market is political and financial.

A strong future with short-term uncertainties

Even by taking only into account our realistic scenario, we can estimate that the mini-grid market should at least experience a 20% CAGR over the next 6 years globally. The growth of this market is not limited by its potential or by companies’ and countries’ willingness to develop those systems but rather by technical and financial issues. The business model for privately operated mini-grids has not been proven yet and most of the projects rely on national or international subsidies. They are therefore strongly impacted by political instability and international programs.

Furthermore, the harsh environment for most mini-grids raises a need for more reliable solutions that can lower project maintenance without increasing its initial cost. New component technologies (e.g. batteries, EMS…) favored by new integration models (e.g. containerized standardized mini-grids) are the main drivers to solve those issues today.

Baptiste Possémé, Senior Consultant

Benjamin Lasne-Laverne, Junior Consultant

Infinergia

You must be logged in to post a comment.