On the occasion of World Water Day, Afrik 21 raises this issue. “Why is sustainable sanitation in African cities important”? Three answers: the preservation of people’s health, the preservation of the environment and resources, and the prevention of natural disasters such as floods.

Africa is still far behind in all these areas. In all countries south of the Sahara, for example, barely 28% of the population has access to basic sanitation facilities and 32% still practise open defecation. This faecal sludge ends up in the waterways, where these same populations get their water, leading to the spread of diseases such as neglected tropical diseases (diarrhoea, cholera, typhoid, etc.). “In Nigeria, for example, diarrhoea causes the death of more than 70,000 children under the age of five each year,” says the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). With 36% of the population indulging in unrestrained behaviour, Mozambique is also among the sub-Saharan African countries where open defecation remains very high.

Senegal is one of the few countries south of the Sahara that have realised the urgency of the situation, which has been exacerbated by the health crisis caused by Covid-19. Access to sanitation is a reality for 67.4% of the urban population of this West African country. Senegal has achieved this level through the application of standards ISO 30500, ISO 24521 and ISO 31800. ISO 30500 sets out specifications for new domestic toilets that treat waste on site, while ISO 24521 provides recommendations for improving the quality of services and the safe management of sanitation services. ISO 31800 specifies requirements to ensure the performance, safety, operability and maintainability of faecal sludge treatment units,” said El Hadji Abdourahmane Ndione in an opinion piece on Afrik 21 in November 2020. All these standards aim to introduce the necessary requirements for the quality and safety of sanitation infrastructures and systems.

With the difficulties of accessing a safe source of water for sanitation, some African countries are focusing on more environmentally friendly solutions. In Uganda, for example, the Professional Town Planning Association of East Africa (Pupaea) plans to install one million eco-friendly toilets in rural and suburban areas by 2030.

compost toilets©franciscojorgan/Shutterstock

To stop open defecation, which affects 29% of the population in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the Swiss association Stay Clean, in collaboration with the government, also launched the construction of compost toilets in November 2020. These Stay Clean facilities do not use water to flush faeces. The use of these dry toilets also simplifies the treatment of water in sewage treatment plants, as the bacteria and chemicals present in excrement require longer treatment to be as harmless as grey water (wash water).

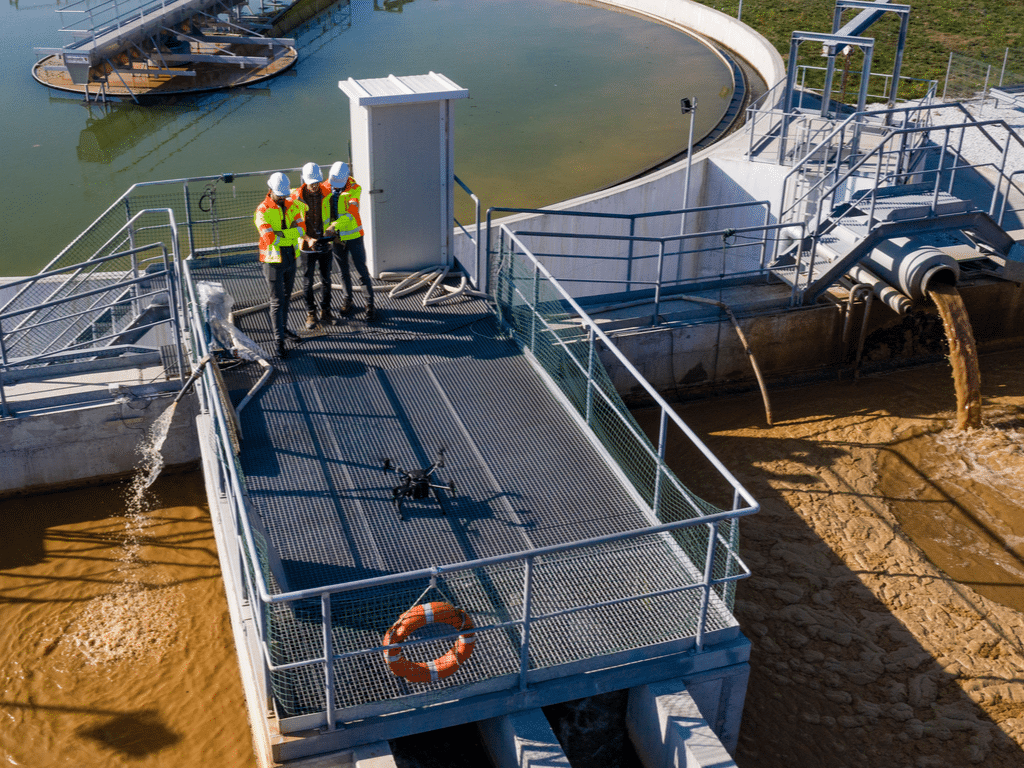

Wastewater management

Apart from faecal sludge, other wastes such as sewage sludge, petroleum waste, plastic bottles (…) also end up in waterways in Africa, clogging the drains. This prevents rainwater from flowing normally, leading to flooding.

In Ivory Coast, for example, the government is implementing the Urban Sanitation and Resilience Project (Paru). It will allow for the construction or rehabilitation of drainage systems for better channelling of rainwater in the most exposed neighbourhoods such as Yopougon and Abobo, the two most populated neighbourhoods in Abidjan, as well as Grand Bassam.

The discharge of untreated industrial effluent into rivers in Kano, Nigeria, also causes significant damage to its riverbeds, adjacent agricultural land, and contamination of groundwater and dam water reservoirs. In order to clean up the rivers in Kano, three wastewater treatment plants are currently under construction in the West African country.

The municipality of Walvis Bay in Namibia is building a plant to treat its wastewater. The plant will be the second of its kind in the country, after the one inaugurated in Windhoek in 2002.

Like Namibia and Nigeria, Ghana, Angola, South Africa, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia and Kenya are already engaged in wastewater treatment plants, although the practice is still in its infancy. Yet the situation is objectively urgent. Lake Victoria, for example, is inexorably deteriorating, day after day, because of pollution from wastewater from industries and households in the large cities of the countries bordering this beautiful and large body of fresh water, notably Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda.

While wastewater treatment plants are paradoxically still very rare in sub-Saharan African countries, given the risks incurred by the populations, the situation is quite different in North Africa.

The multiplication of wastewater treatment plants in the North

Egypt implements a strict policy to preserve its resources. The country has been able to improve the management of its wastewater through the multiplication of wastewater treatment plants. Its Al Mahsamma wastewater treatment plant was awarded the prize for the “best water recycling and reuse project in the world in 2020“ by the magazine Capital Finance International. Located in the governorate of Ismailia in Sinai, the facility covers an area of 42,000 m2, with a capacity of one million m3 per day.

Wastewater that comes out of two pipes©Aleksandr Kurganov/Shutterstock

The Egyptian government is currently implementing a project to expand and modernise the Alexandria West wastewater treatment plant. With a capacity of 460,000 m3 per day, the plant only treats wastewater in one stage: decantation with primary sedimentation. The water is then discharged via the Al-Omoum drainage canal, adjacent to the port of Alexandria. The aim of the project is to expand the treatment plant by adding new units to treat at least 600,000 m3 of wastewater per day. In addition, secondary treatment will be applied to the wastewater, allowing it to be reused. The treated water can then be used for the maintenance of Alexandria’s green spaces or for agriculture. It is understood that tertiary treatment would have been absolutely necessary for the reuse of treated wastewater for market gardening.

In its strategy, Egypt benefits from the partnership with several players, notably Suez. Since March 1st, 2021, the French environmental giant has been operating and maintaining the Gabal El Asfar wastewater treatment plant, which has a capacity of 2.5 million m3 per day in Cairo. The contract, under which Suez is working with local company Arab Contractors (ArabCo) for a period of four years, will also allow for the treatment of the sludge produced by the plant, which will be used to produce biogas for the generation of electricity, which in turn will power the plant itself.

Located in the same sub-region as Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia also have a proactive wastewater management policy. The Tunisian government, through the Office National de l’Assainissement (Onas), is planning to delegate the public service of wastewater management in the greater Tunis area and the governorates of Gabès, Médenine, Sfax and Tataouine. To date, Onas manages 17,500 km of wastewater collection network connected to 795 pumping stations and 122 treatment plants in Tunisia.

The other North African countries, notably Algeria, Libya, Mauritania and Sudan, are still not very active or not at all in wastewater treatment, yet the urgency today is to preserve the environment at all levels.

Reducing soil pollution

Preserving the environment in Africa will also require the collection of solid waste (plastic, electronic, cocoa, palm, pineapple, etc.), as some of this rubbish pollutes streets and neighbourhoods and ends up in waterways or clogging up rainwater drains, causing flooding.

Among the countries most affected by this phenomenon of insalubrity on the continent are Mali, Niger, Ethiopia, Congo, Chad, Tanzania, Burkina Faso, Mozambique and Nigeria. And when it comes to waste treatment, these countries are no further ahead.

The urgent need today is to build an integrated waste management system. For each sanitation project, the emphasis must be placed on both the collection and treatment of waste. This will prevent tragedies such as explosions in landfills, collapses of dumps or landslides as happened at the Koshe landfill in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 2017. It will also help combat global warming by limiting the accumulation of organic waste in methane-emitting landfills.

And how do we do it?

The creation of the integrated waste management chain will be done with all the links in the chain. While in previous years the focus was on waste management by government enterprises, more delegation will be required, especially to the private sector. Informal activities should also be encouraged at the neighbourhood level.

A state like Morocco produces six million tonnes of waste per year, an average of about 250 kg per capita. This North African kingdom is decentralising its waste management. In February 2019, for example, Averda Morocco was chosen by the municipality of Tangier to manage its waste for a period of 20 years. Averda’s subsidiary, based in the United Arab Emirates, recently inaugurated a waste treatment unit in the municipality.

A waste treatment unit ©moxumbic/ Shutterstock

Ghana is also a leader in waste collection and treatment. For many years, Zoomlion has been providing public waste management services in several cities in this West African country. The subsidiary of the Jospong Group, for example, is working with the Ghanaian government on projects to build waste treatment plants, including in Sefwi Wiawso. The plant in the North West region will be able to process 200 tonnes of solid waste per day.

Benin is also investing to improve solid waste collection. The government of this West African country has just equipped the Société de gestion des déchets solides et de la salubrité du grand Nokoué (SGDS-GN) with 20 trucks to improve the collection and transport of solid waste in the Grand Nokoué. According to the SGDS-GN, 358,000 tonnes of waste are produced each year in Grand Nokoué. However, only 10% of this waste is collected. The remaining 90% is dumped in nature, causing pollution of land and waterways. However, Benin still needs to work on waste treatment.

Inès Magoum